"Welcome to Hillend Loch." Asmarina's voice shakes slightly as she addresses the women on the old minibus, its engine still rattling as it cools. "The route I have chosen as today’s walk leader is roughly 2 hours.” She rushes on, trying to remember the notes she had written out over and over. “Hillend Loch was created in 1797 and was the largest reservoir in the world for some time. It supplied water to the steel and paper mills in Airdrie and Coatbridge along the Monklands Canal. Now, it provides fresh water for people in the area.” She glances at Sandra, sitting at the wheel, who gives her an enthusiastic thumbs up. “Hillend Loch is a popular spot for recreational fishing and birdwatching. It is home to various species such as kingfishers, otters and migratory birds like swallows." She pauses, having reached the end of her first page of memorised notes, but the ladies are smiling up at her, waiting for more. “Um, shall we get going?’”

“What’s the theme?” Farah shouts to Asmarina from the back of the bus.

“Oh yes. Today’s mindful meandering theme is - Water.”

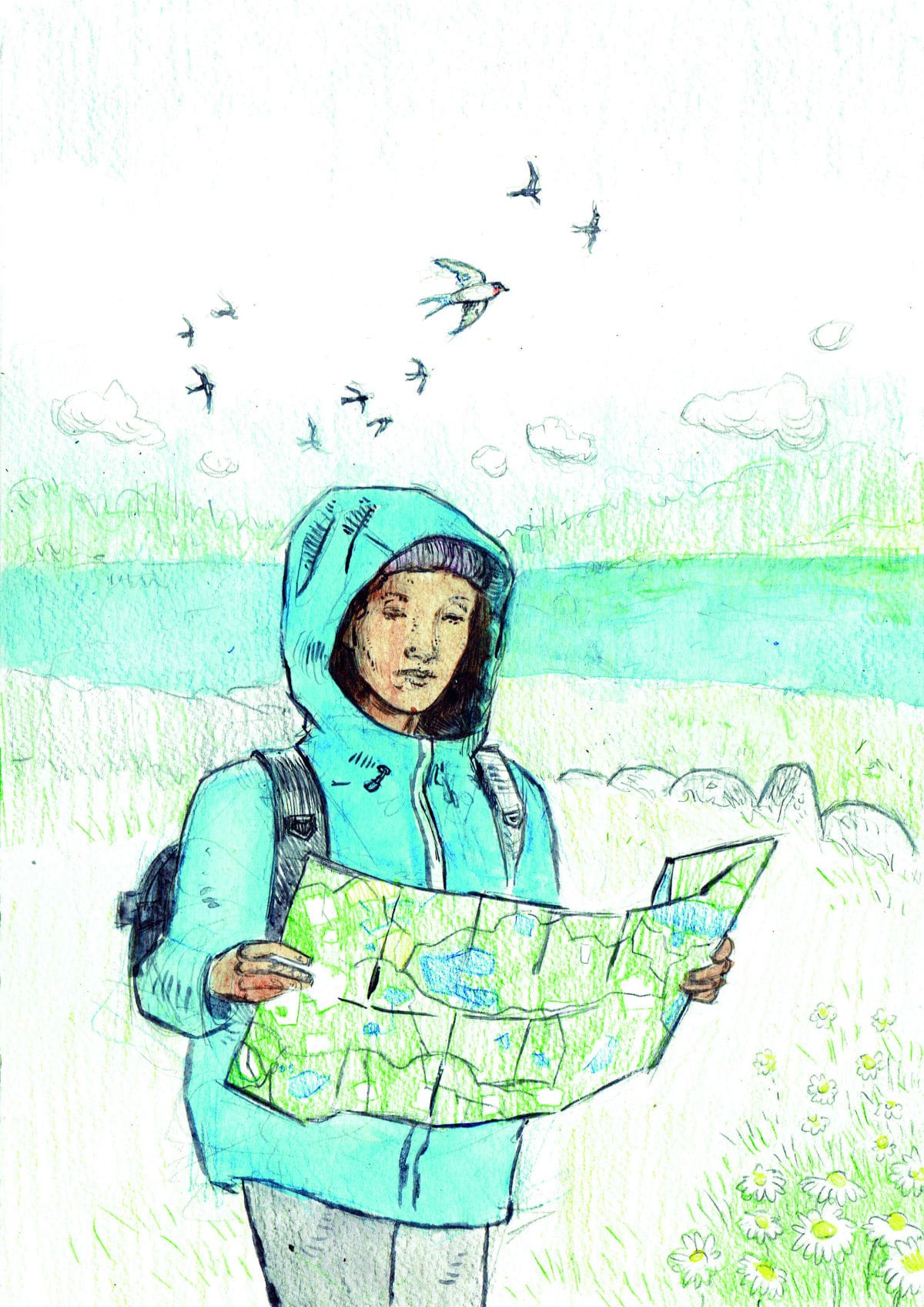

With that, the women pull on waterproofs and pass around a bag of sweets before Asmarina leads them off the bus towards the loch, glancing at the printed-out map in a plastic poly-pocket as she goes.

Asmarina joined the Mindful Meandering Women’s Group after her friend Farah's recommendation at the school gates last winter. Every other Tuesday since, she has met these women to walk around picturesque locations in North Lanarkshire and beyond. They’ve explored paths in the Kilsyth Hills, the Campsie Fells, and the Old Strathkelvin Railway line, and even ventured up to Loch Lomond once, hurtling down single-track roads in the rattly old minibus, which Sandra rents from the local youth club. Scotland's beauty is often enjoyed soaking wet, but thanks to Sandra's grant for all-weather gear, their walks are now significantly more fun and much less soggy.

Like many women in the group, she settled here as a refugee, but while others share their stories, Asmarina remains dammed up; she’s afraid that if she starts, she’ll never stop, and they’ll pour out of her uncontrollably. But that’s what’s good about this group; there's an unspoken understanding between them and as Sandra says, it’s mindfulness - just enjoy nature and be.

Sandra, the community worker who organises the logistics, is also a mindfulness coach, so they often do gentle exercises as they walk. Asmarina's favourite is counting five things you can see, four things you can hear, three things you can feel, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste. She does it with her daughter on the school run, who loves it, especially since finding something to taste is tricky - they usually settle for chocolate.

Group members can volunteer to lead a walk, taking charge of the whole experience, from route planning to researching and risk-assessing with Sandra. Asmarina had procrastinated about leading; it felt monumental somehow. Sandra always said, "Remember ladies, as leaders, we pave our own paths," and "Taking charge is a declaration of strength, resilience, and unity!"

She can’t put it off any longer, today is her time.

“Gather around everyone.” She has stopped the group under some trees along the bank of steel-coloured loch, its outline blurred by fine drizzle. Nearby, fishermen cast their lines while a bouncy dog splashes through puddles. Asmarina pulls a flask from her backpack and pours a little honey-coloured tea into paper cups, one for each of the women.

"Our first exercise is to drink mindfully. I made this tea at home with my daughter. I couldn't believe my eyes when I saw this flower growing in Scotland. At home, it's a meadow flower called gwa-lət, known for its relaxation properties. Can anyone identify the plant by its smell?"

The women stand in a loose circle, holding the steaming cups, and take long, purposeful sniffs. "It's chamomile?" Sandra beams, "Sleepy tea!"

"Correct!!" Asmarina is beginning to enjoy herself. "I would like you to drink this as slowly as possible and focus on the different sensations as you do. It’s ok if you notice your mind wandering; just try to bring your attention back to the feeling of drinking this tea."

The women take their cue from Asmarina as she closes her eyes and begins to sip. She enjoys the warm tea, but it floods her with memories, and within moments, her mind is elsewhere. She thinks about thirst - there's a kind of thirst that's gnawing, all-consuming, a thirst that kills. She wonders if the other women are remembering it, too.

She grounds herself, feeling the warmth of the cup in her hand. She reminds herself about where she is, next to what was once the biggest freshwater reservoir in the world, whose purpose now is to provide for people who may never know thirst as she has.

After the tea and cups are packed away, the walk continues to the south. Farah starts to talk about a particular sweet tea she had as a child, and the women follow, reminiscing about home flavours and childhoods - a different purpose in their steps.

As they follow the path, swallows flit about, their movements quick and purposeful among the reeds and marsh beds. They are about halfway through their walk when they encounter a man in green wellies striding confidently in the opposite direction, accompanied by three handsome dogs.

“Hello, ladies,” he bellows. “Just to warn you, the path peters off just past the next turn. Probably best to turn back.”

The women instinctively turn to their leader, and Asmarina feels anxiety creeping in. She checks the map clutched in her hand, but the rain has got in and smudged the ink, so she can’t see if there is an alternative route.

“That’s a shame,” Farah says bracingly, “but at least we’re not lost, and we’ve had a lovely walk.” Asmarina stands tall and steps forward, determined.

“You came from that direction, so you managed to get through.”

“Yes I did,” he replies, puffing out his chest. “But it’s rough going, not for the faint-hearted…” he trails off, leaving the implication hanging in the air.

Asmarina stays put, calm and collected. The man begins to fidget; does he understand? Can he see in Asmarina’s eyes a glimpse of what she's endured? The barriers she's pushed, the people she's lost, the sickness, the fatigue, the bureaucracy, the baking deserts, the flimsy freezing tents, the dark seas, the many, many borders.

Maybe, just maybe, he gets a sense of it as he nods and continues on his way.

Not long after, the women make their own way quietly and quickly, through ankle-deep mud, and help one another over a fallen tree. Each of them is now determined to complete the journey as planned.

On the home stretch the sun suddenly breaks through, and the women take down their cagoule hoods to enjoy the warmth. The swallows have rejoined them, circling the women and picking off the flying insects stirred up by the group’s passage through the tall grasses and low branches.

They arrive at the head of the loch and watch the swallows silently for a while, twisting and spinning through the air, swooping low so their little bodies reflect in the steely water. Without disturbing the peacefulness, Asmarina speaks. “In the summer months, Hillend Loch’s fresh water and insect-rich environment is the perfect place for barn swallows to refuel or end their migration. These birds will have only just arrived after flying around 7,000 miles from Sudan, Somalia or my country, Eritrea. They have travelled in extreme environments through often treacherous conditions. Let’s take a final moment together to reflect on the resilience, unity and strength it has taken for them just to arrive.